Well, having gotten the opportunity to watch “The Metaphysical Engine, Or: What Quill Did,” I think I can agree with Phil Sandifer’s review of the episode. It’s quite the hot mess. A really cool hot mess with loads of crazy and fascinating sci-fi ideas.

The story is balls out, whack-daddy, batshit crazy. But kind of ridiculous. Just the kind of crazy that Doctor Who has been good at since the early days.

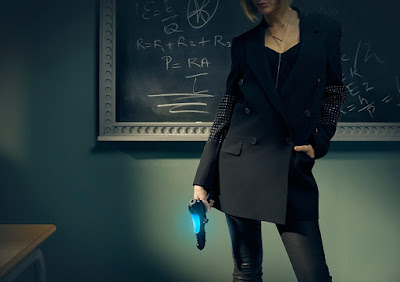

To the audience, Quill has a very deceptive demeanour. Kelly’s physicality appears very cold and distant in the initial promotional material. They shoot her like an ice queen, and her behaviour in the early episodes displays a cold, manipulative aggressiveness.

Rage peeks out from Quill’s stony physiognomy occasionally. As do all her passions. Her genocidal anger at the Shadowkin. The desperate eros of her kiss with the android in “The Coach With the Dragon Tattoo.” The giddy glee of driving a bus into a grotesque alien tentacle.

Patrick Ness cheekily subtitled this episode “What Quill Did.” It’s a joke, a counterpoint to the bottle episode of the under-25s cast* stuck in their classroom in a nameless void.

* Class is positively 90210 in casting adults as teenagers. Charlie’s Greg Austin is 24. Fady Elsayad is 23. Vivian Oparah is 19, but she plays a 14 year old. April’s Sophie Hopkins is 26 years old and plays someone who just turned 18.

She has to, because the episode is a ridiculous Maguffin chase. It succeeds only because its actors are totally dedicated to its madness.

More than just saving the episode from collapsing into a pile of disjunctive nonsense flying away in all directions, Kelly’s charisma as Quill effects a very important transformation in how the audience sees the show.

Heroes and Villains

I’ve come back several times to the moment in the first episode of Class, “For Tonight We Might Die,” where the Doctor admonishes Quill for a crime. She defends herself as a freedom fighter, because she’s long become accustomed to people calling her a criminal because of her guerrilla campaign against Rhodia’s monarchy.

But the Doctor’s upset with her because of how she tricked a Coal Hill student into killing himself firing Quill’s self-sacrificing Rhodian gun at a Shadowkin. The point of the moment is that Quill is not the self-evidently obvious villain that Charlie’s described her as.

The Doctor is the ethical compass of Doctor Who’s universe, and if he sympathizes with you, it’s a sign that you’re in the right. At least in part.

Because the under-25s are absent from this episode, we can let ourselves sit with Quill without interruption. She’s in every scene of “The Metaphysical Engine,” carrying the story almost entirely on her own.

This has never happened during the entire run of Class so far. She’s essentially locked the under-25s away where their ensemble can self-destruct and she’s taken over the show.

More than that, she deserves to take over the show by the time “The Metaphysical Engine” finishes. Though it constitutes

SPOILERS

to say so, this episode is her emancipation story. We’ve been shown how much Quill is willing to risk for her freedom from the biological weapon in her brain, enslaving her to Charlie.

The show has challenged Charlie on his treatment of Quill before, most obviously in “Co-Owner of a Lonely Heart.” So we’ve been primed to a more sympathetic view of Quill than the show first gave us when she was Charlie’s ice queen bodyguard and the most psychotic physics teacher you’ve ever had.

So if Quill has become a hero, Charlie would become even more villainous in contrast. It completes the journey from his squeaky clean appearance at the start of the series, through his critiques from Tanya and Matteusz, through his immense guilt and rage in “Detained.”

More than that narrative role, it shows more profoundly than Class has ever done yet what the nature of heroism is.

Right and Wrong

Because when you think about it, Quill has always been in a subject position. Consider the fact that Charlie – her literal master – always calls her by her surname. A surname that’s also the name for her people. It would be like calling someone “Black” or “China” as their name.

Considering that Andr’ath’s rebellion was the uprising of an oppressed class on Rhodia, there’s probably plenty of racism in Charlie’s condescension toward her. So while Charlie’s been positioned as the hero from the early press materials through the show’s first episodes, Quill is the most sympathetic figure according to all our political moralities.

She is a freedom fighter, and “The Metaphysical Engine” was her most intense fight for freedom yet. As an agent of liberation from racism, monarchy, and slavery, there’s no more pure representative of the good and of freedom than her.

Charlie has entered the role of oppressor, and Quill depicted completely as a freedom fighter.

The everyday contributions of a multi-disciplinary writer and researcher to his own projects

Will the Liberal Finally Die or Regenerate? Research Time, 29/11/2016

Life has gotten a bit busy, so my Class review will be late by a day or two. Judging by Phil Sandifer’s review of the episode, I’m not missing on much artistically, but it will probably be a fascinating shit show of crazy ideas flying all over the place.

Such things have their place in science-fiction, and in the world of Doctor Who as well.

But today, I want to follow on from yesterday’s post about the CBC controversy brewing. Right now, Canada is experiencing a white nationalist movement, just as in Trump’s triumph in America and the growing movements in Europe.

You might not think so because of Justin Trudeau’s leadership. How can there be a resurgence of political racism in Canada when we re-elected the party with contemporary multiculturalism at its core, led by a fresh-faced social progressive?

Justin Trudeau himself is a frightfully normal Liberal Party politician. He campaigned as a standard-bearer for social progressivism and institutional change to the Canadian state after the paranoid doldrums of the Harper decade. He’s ended up a new mix on traditional Liberal Party hypocrisy, walking back all his promises that would actually change Canadian institutions and economic relationships.

Trudeau will dominate Canadian state politics for the next three years at least, probably longer. But the white nationalist movement has its own voice in federal politics in Kellie Leitch.

Canadian white nationalism is specific to the Canadian situation. But a white nationalist reactionary movement tends to emerge in response to a wave of activism for formerly excluded people to be included as full members of a society.

America’s largely revolves around the growing social clout of black and Hispanic minorities, and activists from those communities who seek material equality as people and as cultures.

The different European white nationalist movements respond to the demands of immigrant groups for inclusion. They first emerged when the groups were from the former colonies, but picked up popular speed when the mass influx of Muslim refugees from the three/four wars* of the Middle East began.

* The Libyan Civil War, the Saudi-Iran proxy war for control of Yemen, and depending on how you divide the conflict, the uprising against Bashar al-Assad, and the Syrian-Iraqi war on ISIS.

In America, it was a renewed desire of the former slave class for social inclusion – the demand that black lives matter. In Europe, it was the demand of Muslim people to become Europeans, when Europe has been defined since the early second millennium in opposition to Islamic civilization.

Canada? I still have some work to do tracing the ideas, but my initial hypothesis is that Canada’s conservative culture started to embrace white nationalism in response to the Indigenous cultural renaissance. The Canadian state was founded – in part, but in essential part – as institutions to remove Indigenous people from political life.

Lock them away in reserves, in rural areas where no one goes. The first major crime of the Canadian state was the suppression of francophone Indigenous people in the first mass settling of the territories of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. State-sponsored genocide continued through the residential schools.

The last five years have seen the recognition of these crimes, and the growing visibility of continuing racism. When an elected official in Saskatchewan reacts to the murder of a young Indigenous man by declaring that the shooter should have killed all Colten Boushie's friends so there’d be no witnesses? He got in trouble, but he was speaking for his constituents.

Chantal Mouffe writes in praise of liberalism because of one important aspect of its philosophy – the possibility that everyone can be included in a society, no matter how different they are. That community can arise from difference, not from conformity to some common moral, religious, or ethnic being.

In the wake of Trump’s election, there’s been a lot of chatter among self-identified liberals that maybe it’s time to move on from “identity politics.” To move away from provoking the white people who are threatened by the racially marginalized seeking inclusion.

Because mainstream liberalism sees racism as a matter of individual’s or group’s shared beliefs about people, it’s often blind to more structural material oppression. Yet liberalism’s drive to include difference requires confronting and changing those systematic institutional structures that perpetuate racializing inequities.

If liberalism and liberals accept and reconcile their politics with nationalism, liberal politics will die. If liberal thinkers and leaders find ways to fight nationalism – to welcome the different and find strength in that diversity and bravery in confronting fundamental structures in society? It will regenerate into a more powerful philosophy and a more peaceful world.

Such things have their place in science-fiction, and in the world of Doctor Who as well.

But today, I want to follow on from yesterday’s post about the CBC controversy brewing. Right now, Canada is experiencing a white nationalist movement, just as in Trump’s triumph in America and the growing movements in Europe.

You might not think so because of Justin Trudeau’s leadership. How can there be a resurgence of political racism in Canada when we re-elected the party with contemporary multiculturalism at its core, led by a fresh-faced social progressive?

Justin Trudeau himself is a frightfully normal Liberal Party politician. He campaigned as a standard-bearer for social progressivism and institutional change to the Canadian state after the paranoid doldrums of the Harper decade. He’s ended up a new mix on traditional Liberal Party hypocrisy, walking back all his promises that would actually change Canadian institutions and economic relationships.

Trudeau will dominate Canadian state politics for the next three years at least, probably longer. But the white nationalist movement has its own voice in federal politics in Kellie Leitch.

Canadian white nationalism is specific to the Canadian situation. But a white nationalist reactionary movement tends to emerge in response to a wave of activism for formerly excluded people to be included as full members of a society.

America’s largely revolves around the growing social clout of black and Hispanic minorities, and activists from those communities who seek material equality as people and as cultures.

The different European white nationalist movements respond to the demands of immigrant groups for inclusion. They first emerged when the groups were from the former colonies, but picked up popular speed when the mass influx of Muslim refugees from the three/four wars* of the Middle East began.

* The Libyan Civil War, the Saudi-Iran proxy war for control of Yemen, and depending on how you divide the conflict, the uprising against Bashar al-Assad, and the Syrian-Iraqi war on ISIS.

In America, it was a renewed desire of the former slave class for social inclusion – the demand that black lives matter. In Europe, it was the demand of Muslim people to become Europeans, when Europe has been defined since the early second millennium in opposition to Islamic civilization.

Canada? I still have some work to do tracing the ideas, but my initial hypothesis is that Canada’s conservative culture started to embrace white nationalism in response to the Indigenous cultural renaissance. The Canadian state was founded – in part, but in essential part – as institutions to remove Indigenous people from political life.

Lock them away in reserves, in rural areas where no one goes. The first major crime of the Canadian state was the suppression of francophone Indigenous people in the first mass settling of the territories of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. State-sponsored genocide continued through the residential schools.

The last five years have seen the recognition of these crimes, and the growing visibility of continuing racism. When an elected official in Saskatchewan reacts to the murder of a young Indigenous man by declaring that the shooter should have killed all Colten Boushie's friends so there’d be no witnesses? He got in trouble, but he was speaking for his constituents.

Chantal Mouffe writes in praise of liberalism because of one important aspect of its philosophy – the possibility that everyone can be included in a society, no matter how different they are. That community can arise from difference, not from conformity to some common moral, religious, or ethnic being.

|

| I may sound alarmist when I say this, but now is a time when alarmism is entirely reasonable. As Canadians, we have to accept that a not insignificant number of our fellow Canadians think it's not only morally acceptable to kill Indigenous people, but that it's a national imperative to suppress, marginalize, and drive Indigenous people to their cultural and literal death. |

Because mainstream liberalism sees racism as a matter of individual’s or group’s shared beliefs about people, it’s often blind to more structural material oppression. Yet liberalism’s drive to include difference requires confronting and changing those systematic institutional structures that perpetuate racializing inequities.

If liberalism and liberals accept and reconcile their politics with nationalism, liberal politics will die. If liberal thinkers and leaders find ways to fight nationalism – to welcome the different and find strength in that diversity and bravery in confronting fundamental structures in society? It will regenerate into a more powerful philosophy and a more peaceful world.

Who Is the Public You Broadcast? Advocate, 28/11/2016

Or: How the CBC Fights White Nationalism by Existing

Just a few paragraphs of riffing on the politics of Canada. In part, it’s to escape to a world of news not dominated by Trump and Trumpism. But I can also see the embrace of extremity that he’s inspired. Which is depressing to me as a person.

Late last week, the complete dismantling of Canada’s public broadcaster the CBC has become an ordinary mainstream discussion. Because two leading candidates for our Conservative Party leadership, Kellie Leitch and Maxime Bernier, announced that a part of their platform is radically changing that institution.

It has a regional network providing local programming – for news and entertainment – from all over the country. A bureau for every province and every major population centre in that province. It runs television, radio, and internet services for each of those regions.

CBC’s television service gets less than 5% audience share for the entire country. We aren’t exactly dealing with a powerhouse of television production like the BBC. But it essentially provides a media production house and budget to every significant region of Canada.

It’s especially important for more isolated regions of the country, throughout the north and rural regions. These are lands so vast that it’s difficult to get any viable local media production happening there. Places where a private network, with its incentives to focus only on the largest, richest markets, would never have an incentive to send anyone.

Leitch and Bernier both say that the CBC is a government intrusion into the media market. A monopoly whose removal from the commercial television game would spur competition that’s now stagnant.

How the disappearance of a television network that barely gets 5% audience share would spur competition is anyone’s guess.

Bernier would prefer that the CBC become an equivalent to PBS in the United States. There’d be a little government funding, but most of its production would come through private donations. It could probably only afford one or two studios and produce only a few, very low-budget, productions.

Leitch wants to dismantle and sell the entire network. The CBC would provide some rural radio coverage for local concerns at most.

Under all this talk of the CBC as a government “monopoly” on a media market, is a voice in mainstream discussion of long-simmering right-wing populist hatred of the CBC. A government-built network that constantly opposes conservatism, a mouthpiece for liberal and Liberal Canada.

The radical conservatives of my country have a long and colourful history of hating the CBC for its supposed liberal bias. And quite a few on the left found the network hopelessly corrupt and kowtowing to the Conservative Party line during the Harper years.

The drive to dismantle the CBC is to destroy what radical conservatives consider an ideological opponent.

And there’s an even deeper, more disgusting idea at the heart of radical conservative hatred for the CBC. Remember that regional network of local studios I mentioned? Those low-budget production houses scattered all over the country provide a channel for voices in the very rural north and wild areas of the country to speak.

The ongoing Indigenous Cultural Renaissance of Canada exploded in artistic and political vectors across the country through those channels. Indigenous voices today demand material reparations for acts of genocide. They demand control over their lands – constitutionally speaking, sovereignty within the Canadian state.

They demand recognition as equal participants in Canadian culture – not just as individuals, but as individuals whose singular character was shaped by their Indigenous culture. The Indigenous want in.

Indigenous voices reach the hearts of Canada’s biggest cities and smallest, whitest towns through the communication networks of all those CBC studios. They’re being carried by private channels now, having built these relationships with their newfound cultural power. But the CBC was the first conduit, and it remains one of the most important.

The radical conservative line on the CBC is that it’s a home for urbane, alienated, socially progressive (and Liberal sellout) elites. And there are a lot of hipster journalists working for the CBC today. Dismantling CBC will likely shut many left-wing voices out of mainstream media.

But if the CBC is dismantled, it will also significantly diminish the Indigenous voices reaching the rest of Canada. It will be easier for Indigenous people to be kept silent, confined in the wilderness where proper Canadians never go. To the silent, dark, and cold.

One of the advantages Trump’s moving the Overton Window is that the enemies of racism can return to calling what we fight what it really is. Racists aren’t the only ones who dog-whistle. If you were speak in code to disguise white nationalism, we have to speak in code to call you out on it. Otherwise, we’d look extreme and lose credibility.

So thank you Donald Trump, for letting me say what seems to be the real motivations of Kellie Leitch, Maxime Bernier, and quite a few (though not all) of the folks who support exactly the sorts of proposals they now say openly.

If you dismantle the CBC, you’ll know that the Indigenous voices of Canada will lose a lot of their local media production outlets, and media communication between your world and the mainstream of Canada. It will be easier to remind Canada’s Indigenous of their proper place in Canadian society.

Absent from it.

Just a few paragraphs of riffing on the politics of Canada. In part, it’s to escape to a world of news not dominated by Trump and Trumpism. But I can also see the embrace of extremity that he’s inspired. Which is depressing to me as a person.

Late last week, the complete dismantling of Canada’s public broadcaster the CBC has become an ordinary mainstream discussion. Because two leading candidates for our Conservative Party leadership, Kellie Leitch and Maxime Bernier, announced that a part of their platform is radically changing that institution.

It has a regional network providing local programming – for news and entertainment – from all over the country. A bureau for every province and every major population centre in that province. It runs television, radio, and internet services for each of those regions.

CBC’s television service gets less than 5% audience share for the entire country. We aren’t exactly dealing with a powerhouse of television production like the BBC. But it essentially provides a media production house and budget to every significant region of Canada.

It’s especially important for more isolated regions of the country, throughout the north and rural regions. These are lands so vast that it’s difficult to get any viable local media production happening there. Places where a private network, with its incentives to focus only on the largest, richest markets, would never have an incentive to send anyone.

Leitch and Bernier both say that the CBC is a government intrusion into the media market. A monopoly whose removal from the commercial television game would spur competition that’s now stagnant.

|

| Kellie Leitch has become Canada's leading standard-bearer for the global white nationalist political movement. |

Bernier would prefer that the CBC become an equivalent to PBS in the United States. There’d be a little government funding, but most of its production would come through private donations. It could probably only afford one or two studios and produce only a few, very low-budget, productions.

Leitch wants to dismantle and sell the entire network. The CBC would provide some rural radio coverage for local concerns at most.

Under all this talk of the CBC as a government “monopoly” on a media market, is a voice in mainstream discussion of long-simmering right-wing populist hatred of the CBC. A government-built network that constantly opposes conservatism, a mouthpiece for liberal and Liberal Canada.

The radical conservatives of my country have a long and colourful history of hating the CBC for its supposed liberal bias. And quite a few on the left found the network hopelessly corrupt and kowtowing to the Conservative Party line during the Harper years.

The drive to dismantle the CBC is to destroy what radical conservatives consider an ideological opponent.

|

| Local production houses like CBC Iqaluit, for example. |

The ongoing Indigenous Cultural Renaissance of Canada exploded in artistic and political vectors across the country through those channels. Indigenous voices today demand material reparations for acts of genocide. They demand control over their lands – constitutionally speaking, sovereignty within the Canadian state.

They demand recognition as equal participants in Canadian culture – not just as individuals, but as individuals whose singular character was shaped by their Indigenous culture. The Indigenous want in.

Indigenous voices reach the hearts of Canada’s biggest cities and smallest, whitest towns through the communication networks of all those CBC studios. They’re being carried by private channels now, having built these relationships with their newfound cultural power. But the CBC was the first conduit, and it remains one of the most important.

The radical conservative line on the CBC is that it’s a home for urbane, alienated, socially progressive (and Liberal sellout) elites. And there are a lot of hipster journalists working for the CBC today. Dismantling CBC will likely shut many left-wing voices out of mainstream media.

|

| Aesthetically, my favourite expression of Canada's Indigenous Cultural Renaissance is the music of Tanya Tagaq. Not only is it beautiful, remarkable music unlike anything else most Westerners (and probably most other cultures on Earth) have ever heard. It expresses the same social and political ideas that threaten all the traditional relations of cultural dominance of the Canadian state over Indigenous life. |

One of the advantages Trump’s moving the Overton Window is that the enemies of racism can return to calling what we fight what it really is. Racists aren’t the only ones who dog-whistle. If you were speak in code to disguise white nationalism, we have to speak in code to call you out on it. Otherwise, we’d look extreme and lose credibility.

So thank you Donald Trump, for letting me say what seems to be the real motivations of Kellie Leitch, Maxime Bernier, and quite a few (though not all) of the folks who support exactly the sorts of proposals they now say openly.

If you dismantle the CBC, you’ll know that the Indigenous voices of Canada will lose a lot of their local media production outlets, and media communication between your world and the mainstream of Canada. It will be easier to remind Canada’s Indigenous of their proper place in Canadian society.

Absent from it.

Saving the Liberal Brand, Research Time, 25/11/2016

I’m not talking about the Liberal Party here in Canada, though I might spin out a Sunday post if I have time this weekend about the debate that’s been stirred this week on the future of Canadian public broadcasting. That’s for another time.

Also, I want to see the next few days of yelling in the media about it, to see what new trajectories of public conversation emerge from it. Where our popular opinion seems to be going.

Specifically, think about everything I’ve written about Robert Nozick, Freidrich Hayek, and other elements of the libertarian tradition. Liberalism as politics today is in a weird, fallen, broken state.

Libertarian thinking is the last branch of liberal politics with any idealism or popular energy at all. Every other path of mainstream liberal politics is either hopelessly corrupt or is so wedded to muddling consensus thinking that it can’t deal with true challenges.

You know, like mainstream centrist political parties. Take the Democratic Party in America as an example of corruption. Their leadership is a self-absorbed closed circle of professional electioneers and party staffers.

The Democratic Party of Hillary Clinton, Donna Brazile, and Debbie Wasserman-Schultz is so obsessed with their high-level power brokerage that their entire grassroots electoral machine has collapsed.

socially progressive values. But they’re turning away from all of the most meaningful reforms to the Canadian state that they promised. As well, they’re continuing the destructive fiscal and military policies of the Harper years.

Mainstream liberal political thinking also depends on a principle that can’t work as politics, especially in a volatile, dangerous time like the 2010s. That principle is reconciliation at all costs.

This is an idea I found at the heart of a book of essays by Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political. They were written over the 1990s, criticisms of mainstream liberal politics at a time when liberal capitalism was so triumphant in global politics that some called it the end of history itself.

The end of fundamental conflicts over the nature of the human project. We had settled on our human project, and it was called liberal democratic capitalism. Of course, that didn’t work out for many reasons. One of them is this fundamental flaw in the practical actions of liberal politicians.

The common joke today is that the far left is the side obsessed with political correctness, and that political correctness is nothing but the profusion of feathery technical talk, replacing more ordinary language for discussing race and gender. And the punchline is that all this is to avoid upsetting people.*

The irony is that this is what mainstream liberal political principles are all about. The principles that drove Bill Clinton and Tony Blair’s economic policy approaches – the “Third Way” between socialism and piracy capitalism which ended up enabling the worst piracy capitalism in human history.

Smooth away differences, goes the mainstream liberal philosophy. Split the world into the public realm of politics and the private realm of individual autonomy. Identify every piece of identity, ideology, and idealism that could conceivably cause conflict between people, then put it in that private realm.

Leave the public realm, where legitimate political discussions happen, to the topics where people generally agree. Here’s a typical example of good liberal public politics. Business is good, and while we can disagree over which policies make for a productive business environment, those technical differences over stuff like interest rates and securities law won’t ever become existential threats.

The decadent liberal politics of today is the pursuit of omni-partisan consensus. The only legitimate mainstream political voices become those who already agree on enough fundamental principles that conflict becomes impossible. But this isn’t peace and justice in society. It’s sweeping problems under the rug.

Never thought something as arcane and dull-as-shit as securities law would become an existential crisis in your society? How about when your securities laws that were produces of that omni-partisan consensus become the conditions for what was almost a global economic collapse? Like eight years ago.

The liberalism of omni-partisan consensus can’t even deal with problems that come up in a country’s arcane and technical financial laws. It’s completely fucked trying to deal with radical nationalism, mass scale racist targeting of war refugees, or religious fundamentalism.

All these movements fundamentally disagree with consensus liberalism because they refuse to accept its standards for consensus.

Nationalism refuses to accept that notions of ethnic identity have no place in politics. A huge wave of desperate war refugees puts the entire consensus about citizenship and who deserves the care of the state into question. Religious fundamentalism explicitly politicizes the demands of people’s divine laws.

Liberalism is bankrupt in the face of these problems. We can see that obviously now that all these problems have erupted throughout our society. So it’s interesting to read these essays from Mouffe and see her making these exact criticisms at the moment of liberalism’s apparent triumph.

What’s necessary are looking at how she discovered a liberalism that can actually take on our current challenges of extremism and justice that were embryonic 20 years ago.

I’m going to get into this idea over the next few posts.

Also, I want to see the next few days of yelling in the media about it, to see what new trajectories of public conversation emerge from it. Where our popular opinion seems to be going.

Specifically, think about everything I’ve written about Robert Nozick, Freidrich Hayek, and other elements of the libertarian tradition. Liberalism as politics today is in a weird, fallen, broken state.

Libertarian thinking is the last branch of liberal politics with any idealism or popular energy at all. Every other path of mainstream liberal politics is either hopelessly corrupt or is so wedded to muddling consensus thinking that it can’t deal with true challenges.

You know, like mainstream centrist political parties. Take the Democratic Party in America as an example of corruption. Their leadership is a self-absorbed closed circle of professional electioneers and party staffers.

The Democratic Party of Hillary Clinton, Donna Brazile, and Debbie Wasserman-Schultz is so obsessed with their high-level power brokerage that their entire grassroots electoral machine has collapsed.

socially progressive values. But they’re turning away from all of the most meaningful reforms to the Canadian state that they promised. As well, they’re continuing the destructive fiscal and military policies of the Harper years.

Mainstream liberal political thinking also depends on a principle that can’t work as politics, especially in a volatile, dangerous time like the 2010s. That principle is reconciliation at all costs.

This is an idea I found at the heart of a book of essays by Chantal Mouffe, The Return of the Political. They were written over the 1990s, criticisms of mainstream liberal politics at a time when liberal capitalism was so triumphant in global politics that some called it the end of history itself.

The end of fundamental conflicts over the nature of the human project. We had settled on our human project, and it was called liberal democratic capitalism. Of course, that didn’t work out for many reasons. One of them is this fundamental flaw in the practical actions of liberal politicians.

The common joke today is that the far left is the side obsessed with political correctness, and that political correctness is nothing but the profusion of feathery technical talk, replacing more ordinary language for discussing race and gender. And the punchline is that all this is to avoid upsetting people.*

The irony is that this is what mainstream liberal political principles are all about. The principles that drove Bill Clinton and Tony Blair’s economic policy approaches – the “Third Way” between socialism and piracy capitalism which ended up enabling the worst piracy capitalism in human history.

Smooth away differences, goes the mainstream liberal philosophy. Split the world into the public realm of politics and the private realm of individual autonomy. Identify every piece of identity, ideology, and idealism that could conceivably cause conflict between people, then put it in that private realm.

Leave the public realm, where legitimate political discussions happen, to the topics where people generally agree. Here’s a typical example of good liberal public politics. Business is good, and while we can disagree over which policies make for a productive business environment, those technical differences over stuff like interest rates and securities law won’t ever become existential threats.

The decadent liberal politics of today is the pursuit of omni-partisan consensus. The only legitimate mainstream political voices become those who already agree on enough fundamental principles that conflict becomes impossible. But this isn’t peace and justice in society. It’s sweeping problems under the rug.

Never thought something as arcane and dull-as-shit as securities law would become an existential crisis in your society? How about when your securities laws that were produces of that omni-partisan consensus become the conditions for what was almost a global economic collapse? Like eight years ago.

|

| We democrats will need to engage, refute, and fight the ideas of radical nationalism. Which means we have to study radical nationalists, know them better than they know themselves so we can learn best how to defeat this force forever. If only I could find an English translation of Aleksandr Dugin without ending up on a watch list. I only want to find it so I can know our enemy. |

All these movements fundamentally disagree with consensus liberalism because they refuse to accept its standards for consensus.

Nationalism refuses to accept that notions of ethnic identity have no place in politics. A huge wave of desperate war refugees puts the entire consensus about citizenship and who deserves the care of the state into question. Religious fundamentalism explicitly politicizes the demands of people’s divine laws.

Liberalism is bankrupt in the face of these problems. We can see that obviously now that all these problems have erupted throughout our society. So it’s interesting to read these essays from Mouffe and see her making these exact criticisms at the moment of liberalism’s apparent triumph.

What’s necessary are looking at how she discovered a liberalism that can actually take on our current challenges of extremism and justice that were embryonic 20 years ago.

I’m going to get into this idea over the next few posts.

The Agency of Swarm, Jamming, 24/11/2016

Yesterday’s post ended up mostly being a recollection of my lifelong affiliation with nerd culture, and why I’m trying to move beyond it today. It was a political and ethical post about how nerd culture has become increasingly identified with resentful grievance and hatred instead of creativity and openness.

About how a community of people that considers itself a home for freaks and weirdos became a pit of racism and misogyny. I couldn’t help but meditate on that sad transition as I wrote my explanation* for why I’ve come to presume that geeks and nerds hide horrible, hateful beliefs about everyone around them.

* Which is not an apology for stereotyping that guy on the subway, because I’m not sorry at all.

But I still want to make a few notes here about swarm intelligence. I’m not sure how concepts of swarm intelligence will appear in any of my future work. But when it comes to understanding today’s media ecology and communications infrastructure, getting your head around the concept of swarm is required thinking.

I should start from its agency. That’s the toughest part of swarm intelligence to wrap your head around. We’re accustomed to thinking of intelligence as being wrapped up with self-consciousness, with intentionality.

That is, we think of intelligence as having a direction of attention – at least an ability to direct and focus your attention. An intelligence might not focus their attention all the time – consider when you’re in a deep sleep, or addled by severe sickness like heart attack symptoms or heatstroke, or close to an overdose of some dissociative drug like ketamine.

That’s our intentionality. Imagine an intelligence without intentionality – you’re awake and alert to what’s around you, able to act and react to the affects of your environment. But you have no focus at all. That’s a swarm.

And we usually think of intelligence as being aware of itself. You have some sense of identity. You have a memory of notable past events, and of your close companions among other intelligences – pets, bosses, friends, the older woman who’s always on the evening shift at Tim Horton’s.

And we usually think of intelligence as being aware of itself. You have some sense of identity. You have a memory of notable past events, and of your close companions among other intelligences – pets, bosses, friends, the older woman who’s always on the evening shift at Tim Horton’s.

You remember these relationships, and you have some ability to reflect on yourself – maybe strategize for future plans, maybe wonder about your place in the world or the universe. That’s fundamentally what self-consciousness does.

Now imagine an intelligence without any of that memory and identity. You might have immense power, speed, have an incredibly complicated set of abilities that emerge from the spontaneous movement of your individual parts.

That’s the intelligence of the swarm.

But what are all those individual parts? What makes a swarm intelligence different from the unfocussed, unreflective spontaneous processes that cause intelligent life itself?

What are those processes that literally make me and you and everyone we know? Here are some examples. Embryo development. Everyday metabolism. Cell division. Because a swarm is different from these other spontaneous processes.

The parts of all those unfocussed, unreflective spontaneous processes are all themselves unfocussed, unreflective spontaneous processes.

A swarm's parts are intelligent creatures. Focussed, reflective, planned activities are the processes generating unfocussed, unreflective, spontaneous processes.

Who are these intelligent creatures? A swarm could be composed of viruses, locusts, social media trolls. Or it could be composed of fish, migrating caribou in the middle of a long daytime run through the tundra. The cars and their drivers who manifest a massive traffic jam when one guy hits his breaks for a moment three kilometres up.

A swarm body acts and has intelligence of a kind because it formed and moves in the world, always in response to the affects of its environment. It has that much unity – unity of motion and response. Very simple kinds of action. A collection of intelligent animals move together and constitute a swarm’s parallel of a very simple bacteria.

About how a community of people that considers itself a home for freaks and weirdos became a pit of racism and misogyny. I couldn’t help but meditate on that sad transition as I wrote my explanation* for why I’ve come to presume that geeks and nerds hide horrible, hateful beliefs about everyone around them.

* Which is not an apology for stereotyping that guy on the subway, because I’m not sorry at all.

But I still want to make a few notes here about swarm intelligence. I’m not sure how concepts of swarm intelligence will appear in any of my future work. But when it comes to understanding today’s media ecology and communications infrastructure, getting your head around the concept of swarm is required thinking.

I should start from its agency. That’s the toughest part of swarm intelligence to wrap your head around. We’re accustomed to thinking of intelligence as being wrapped up with self-consciousness, with intentionality.

That is, we think of intelligence as having a direction of attention – at least an ability to direct and focus your attention. An intelligence might not focus their attention all the time – consider when you’re in a deep sleep, or addled by severe sickness like heart attack symptoms or heatstroke, or close to an overdose of some dissociative drug like ketamine.

That’s our intentionality. Imagine an intelligence without intentionality – you’re awake and alert to what’s around you, able to act and react to the affects of your environment. But you have no focus at all. That’s a swarm.

And we usually think of intelligence as being aware of itself. You have some sense of identity. You have a memory of notable past events, and of your close companions among other intelligences – pets, bosses, friends, the older woman who’s always on the evening shift at Tim Horton’s.

And we usually think of intelligence as being aware of itself. You have some sense of identity. You have a memory of notable past events, and of your close companions among other intelligences – pets, bosses, friends, the older woman who’s always on the evening shift at Tim Horton’s.You remember these relationships, and you have some ability to reflect on yourself – maybe strategize for future plans, maybe wonder about your place in the world or the universe. That’s fundamentally what self-consciousness does.

Now imagine an intelligence without any of that memory and identity. You might have immense power, speed, have an incredibly complicated set of abilities that emerge from the spontaneous movement of your individual parts.

That’s the intelligence of the swarm.

But what are all those individual parts? What makes a swarm intelligence different from the unfocussed, unreflective spontaneous processes that cause intelligent life itself?

What are those processes that literally make me and you and everyone we know? Here are some examples. Embryo development. Everyday metabolism. Cell division. Because a swarm is different from these other spontaneous processes.

The parts of all those unfocussed, unreflective spontaneous processes are all themselves unfocussed, unreflective spontaneous processes.

A swarm's parts are intelligent creatures. Focussed, reflective, planned activities are the processes generating unfocussed, unreflective, spontaneous processes.

Who are these intelligent creatures? A swarm could be composed of viruses, locusts, social media trolls. Or it could be composed of fish, migrating caribou in the middle of a long daytime run through the tundra. The cars and their drivers who manifest a massive traffic jam when one guy hits his breaks for a moment three kilometres up.

A swarm body acts and has intelligence of a kind because it formed and moves in the world, always in response to the affects of its environment. It has that much unity – unity of motion and response. Very simple kinds of action. A collection of intelligent animals move together and constitute a swarm’s parallel of a very simple bacteria.

The Ontology of Swarm, A History Boy, 23/11/2016

About Two or Three Months Ago

I took some pictures of a creepy-looking guy on the subway with a bunch of anime and gaming pins on his bag. I didn’t show his face, but I tweeted it with some commentary about how he was probably a fascist.

Over the Weekend

So a few days ago, somebody found this old tweet thread and posted a screencap on a 9gag ripoff forum. And the swarm began.

Starting from about Sunday, I’ve gotten a steady stream of insults from the greater anime-avatar commentariat. It’s been a pretty diverse stream. And as of Tuesday night when I hit “publish,” it’s been chugging along steadily. It’s been 500 mentions and retweets of mentions, and probably a little over 100 original insults.

A lot of sanctimonious call-outs. How dare I call the members of this three-day (and counting) pile-on bullies when I photographed a guy’s bag and made presumptions about his character. I’ve also been called a psychopath, a retard, a jabroni, and a cuck from the global capitol city of cucks.

I’ve never been on the receiving end of this kind of swarm social media attack. I’ve seen them, of course, and read about them and their consequences. But this is the first time I’ve faced a swarm myself. It’s quite fascinating, really.

For one thing – and this is probably a consequence of my long-term exposure to this online culture, its relatively low intensity against me, and my own relative whiteness – the visceral effect of the insults died out pretty fast.

Now, the insults continue. But they became monotonous remarkably quickly, petering out into a steady stream of repetitive noise. The form of the attack is more intriguing to me.

Social media swarms are similar to DDoS attacks, except carried out through the intentional actions of humans. It’s a distributed attack without a central director. The director isn’t human, at least. It's the screencap itself that directs their activity – a signal that points the way to a particular action.

No one in this swarm has done anything other than send a single insult or retweet one or two tweets in the conversation. Then they go away. But there are enough that a steady stream of activity has continued.

Yet while the swarm is composed of complex, intelligent human agents, its action itself isn’t very complicated – a steady stream of repetitive 4chan-stewed insults. Its power is in its brute force – the sheer number of signals cluttering my mentions with acidic contempt.

A Decade or So Ago

I’ve been a nerd all my life. Dorky, socially awkward sometimes, smart, wearing glasses, into weird art like Werner Herzog films and big difficult books. I had a go for a career as a professional academic with a PhD and everything.

And I was bullied a lot as a kid and a teenager – mostly by sports jocks and a few school hoodlums, as well as a couple of classmates who were in treatment for severely violent impulses.

Even after I developed a personality and persona that could get along with pretty much everyone, I saw some pretty awful stuff. When I was 17, my high school’s basketball team put money up among each other for a bet – the winner was whoever could fuck a friend of mine. They thought it was worth a payout because they called her a horse-face.

So when nerd culture took over the culture in the early 21st century with superhero movies, popular sci-fi culture like The Matrix and Doctor Who, Silicon Valley’s prestige, and Dan Harmon’s celebration of misfits Community? I felt proud to have been a nerd. I thought those values – pride in intelligence, love of dorky things, the esteem of misfits and freaks – were good for society.

About Two or Three Months Ago

But geek culture has a dark side. A weirdly racialized, gender-focussed malevolent side. I’ve written about this before, and I’m not the only one. I need only say the words and expect at minimum some googling to refresh your memory – GamerGate, the Quinnspiracy, Hijack the Hugos, the Alt-Right, Mencius Moldbug.

As I saw more and more nerds giving in to the rage and resentment of pick-up culture, misogyny, right-wing libertarian culture, and white nationalism, I’ve lost my ability to identify as a nerd. I mean, objectively, I’m pretty nerdy. I write about philosophy, literature, and sci-fi on a blog constantly.

But the values of so many nerd communities have diverged so much from my own that I can’t really consider myself part of that group anymore. That's why I thought what I thought when I saw that dude sitting next to me on the subway – the new signifiers of an insular, resentful bastard who hates women are anime and sci-fi fandom.

So I’m left digging my Twitter mentions out from under thousands of locust husks, wondering how many people who’ll be in the theatre with me at Rogue One this Xmas sent ape photos to Leslie Jones or rape threats to Anita Sarkeesian.

Of course, the answer will be “Nobody” because all the alt-right nerds will boycott Rogue One for having a woman in the lead role, and my GF and I will be surrounded by hipster geek women enjoying a fine film together.

I took some pictures of a creepy-looking guy on the subway with a bunch of anime and gaming pins on his bag. I didn’t show his face, but I tweeted it with some commentary about how he was probably a fascist.

Over the Weekend

So a few days ago, somebody found this old tweet thread and posted a screencap on a 9gag ripoff forum. And the swarm began.

|

| Well, they finally saw me. |

A lot of sanctimonious call-outs. How dare I call the members of this three-day (and counting) pile-on bullies when I photographed a guy’s bag and made presumptions about his character. I’ve also been called a psychopath, a retard, a jabroni, and a cuck from the global capitol city of cucks.

I’ve never been on the receiving end of this kind of swarm social media attack. I’ve seen them, of course, and read about them and their consequences. But this is the first time I’ve faced a swarm myself. It’s quite fascinating, really.

For one thing – and this is probably a consequence of my long-term exposure to this online culture, its relatively low intensity against me, and my own relative whiteness – the visceral effect of the insults died out pretty fast.

Now, the insults continue. But they became monotonous remarkably quickly, petering out into a steady stream of repetitive noise. The form of the attack is more intriguing to me.

Social media swarms are similar to DDoS attacks, except carried out through the intentional actions of humans. It’s a distributed attack without a central director. The director isn’t human, at least. It's the screencap itself that directs their activity – a signal that points the way to a particular action.

No one in this swarm has done anything other than send a single insult or retweet one or two tweets in the conversation. Then they go away. But there are enough that a steady stream of activity has continued.

Yet while the swarm is composed of complex, intelligent human agents, its action itself isn’t very complicated – a steady stream of repetitive 4chan-stewed insults. Its power is in its brute force – the sheer number of signals cluttering my mentions with acidic contempt.

A Decade or So Ago

I’ve been a nerd all my life. Dorky, socially awkward sometimes, smart, wearing glasses, into weird art like Werner Herzog films and big difficult books. I had a go for a career as a professional academic with a PhD and everything.

And I was bullied a lot as a kid and a teenager – mostly by sports jocks and a few school hoodlums, as well as a couple of classmates who were in treatment for severely violent impulses.

Even after I developed a personality and persona that could get along with pretty much everyone, I saw some pretty awful stuff. When I was 17, my high school’s basketball team put money up among each other for a bet – the winner was whoever could fuck a friend of mine. They thought it was worth a payout because they called her a horse-face.

So when nerd culture took over the culture in the early 21st century with superhero movies, popular sci-fi culture like The Matrix and Doctor Who, Silicon Valley’s prestige, and Dan Harmon’s celebration of misfits Community? I felt proud to have been a nerd. I thought those values – pride in intelligence, love of dorky things, the esteem of misfits and freaks – were good for society.

|

| A recent place where I read about the ontology of swarm attacks was Multitude by Antonio Negri. He was mostly talking about DDoS attacks, but social media harassment mobs move by the same principle. |

But geek culture has a dark side. A weirdly racialized, gender-focussed malevolent side. I’ve written about this before, and I’m not the only one. I need only say the words and expect at minimum some googling to refresh your memory – GamerGate, the Quinnspiracy, Hijack the Hugos, the Alt-Right, Mencius Moldbug.

As I saw more and more nerds giving in to the rage and resentment of pick-up culture, misogyny, right-wing libertarian culture, and white nationalism, I’ve lost my ability to identify as a nerd. I mean, objectively, I’m pretty nerdy. I write about philosophy, literature, and sci-fi on a blog constantly.

But the values of so many nerd communities have diverged so much from my own that I can’t really consider myself part of that group anymore. That's why I thought what I thought when I saw that dude sitting next to me on the subway – the new signifiers of an insular, resentful bastard who hates women are anime and sci-fi fandom.

So I’m left digging my Twitter mentions out from under thousands of locust husks, wondering how many people who’ll be in the theatre with me at Rogue One this Xmas sent ape photos to Leslie Jones or rape threats to Anita Sarkeesian.

Of course, the answer will be “Nobody” because all the alt-right nerds will boycott Rogue One for having a woman in the lead role, and my GF and I will be surrounded by hipster geek women enjoying a fine film together.

Tell Me Your Truths, Class: Detained, Reviews, 22/11/2016

I'm a bit of a theatre nerd. The first long-form work of drama I ever produced was for theatre. So some of my favourite episodes of television are the bottle episodes. “Detained” was the Class bottle episode.

Just a few special effects like the classroom door floating in the blackness of no-space. The CGI shots of the transdimensional asteroids. The explosions and prop chaos during the asteroid crash and other shenanigans with a smoking asteroid. Everything else is carried on the strength of the dialogue and actors.

On those grounds of basic criticism, “Detained” delivers. Patrick Ness’ dialogue has its clunky moments as usual, but all the actors pull off some powerful, nuanced moments. The episode’s entire concept is about forcing the actors into intense literally confessional scenes. This is Doctor Who does No Exit. Literally.

Because,

SPOILERS

warned – they are genuinely in hell. A one-room prison in a pocket beyond space and time where their only way out means confessing their closest secrets about how they feel about each other to each other.

Many Kinds of Truth

So let’s get the basic premise out of the way. Quill puts the Scooby Gang in detention so they don’t mess with her while the events of the next episode are happening. A freaky asteroid smacks their classroom through the rift and knocks them into a no-space.

The asteroid turns out to be a prison for alien murderers. The only way to find out about their situation is to hold onto a piece of the asteroid and let it take you over. And when you channel the asteroid, it forces you into a confession. A suitable piece of mystical police state technology for the Whoniverse.

It isn’t just a matter of being forced to tell the truth. Truth is more complicated than just facts. Because the gang want to learn facts.

They each take their turn with the asteroid so they can learn enough facts about it and their situation to escape – they can each only handle the asteroid once before it fries their brains, the asteroid is a transdimensional prison, they’re trapped in their classroom with the consciousness of a multiple-murderer. And so on.

So far, so Doctor Who. Affordable TV budgets and high drama with cracking scripts, mad ideas, and quality actors. But since I’m doing philosophy at the same time as I’m talking about science-fiction television, I should ask – What kind of truths are we dealing with here?

Each of their interactions goes in the same pattern. They remember the most intense confession they’ve ever made (or almost made) before, then give a similarly intense confession about their friends in the cast, then force the asteroid/prisoner to reveal a secret about their situation.

Truth as Integrity

You confess so that the truth is known, because you’re compelled to say what’s true. This is why confessions are so powerful in the criminal justice – it’s literally the unfolding of truth. The burden of a secret is lost when it’s told. You don’t feel the pain of hiding anymore.

That’s Matteusz’ confession. He recalls coming out for the first time, to his dying grandmother, who knew from the start and didn’t care. The one member of his family who accepted him was the first to be told and also the first to leave. And he was left with the family who kicked him out.

That’s the same nature of his fear of Charlie, of Charlie’s alien nature, morality, capabilities. There is that deep love, but Matteusz’ fear slowly eats away at his love. Saying it lets them work it through and become closer for it. That’s the ethical confession.

Epistemic Truth

A confession is also how you see the world, how you understand what’s happening to you. Tanya’s first confession is of a shameful moment, when she continued to hide the fact that – after stealing a handful of candies as a child – she had planned from the start to steal. While she told her mother that she thought the sweets were free, that at the time she’d understood it not to be stealing.

Tanya’s confession to her friends is also about how she sees the world. She confesses her belief that she isn’t truly their friend because they think of her as a kid sister and not a peer, that they’ll never understand the kind of life and challenges she faces as a black woman in Britain.

What she confesses isn’t true in a factual sense – The rest of the gang are her friends, and while they may not all (except Ram, and oddly Quill) have experienced systemic social racism, as friends they can come to understand it themselves. The bonds of solidarity she doubts are really there.

Tanya’s is an epistemic confession, an expression of her own perspective on the world, which can be mistaken or incomplete while still being true. It’s the truth of how she sees the world.

The Facts

Then there is simply the factual truth. When you know something concrete about your world, and precisely. Typical for Ram, that’s his confession. He’s a stereotypical footballer again that way, always a simple soul. Saying what he thinks and doing what he wants. Heart on his sleeve no matter how hard (and badly) he tries to hide it.

Ram confessed to his father that he had an alien artificial leg. And he confessed to April that he loved her, but knew that she didn’t love him.

There it is. Behold! Check it out!

Responsive Truth

What do we learn from April? She’s a paradoxical character – Phil Sandifer is right that April’s paradoxes and subjective complexity makes her the most intriguing character on Class. But there’s more to these paradoxes.

April is notable for her personal strength to deal with immense burdens and traumas like her link with the Shadowkin and her father’s attempted murder-suicide. But the show first depicted her as this cloying school keener – the only one who cares enough about the school dance to set it up, even though everybody goes.

She doesn’t express her strength on her own. In ordinary situations, she’s content to be passive and unnoticeable, even if she’s lonely or isolated. Her strength only emerges in response to these terrifying challenges. She has a paradoxically weak strength – April is only an agent when she’s reacting.

So her confessions are reactions. She remembers testifying against her father in his criminal trial after his murder-suicide attempt – expressing a terrible, painful truth because the situation itself demands it. A confession that takes immense personal strength to make, but it would never have been made if not forced to.

What forces it? In the original instance, it’s the need to redress a terrible crime – more than having broken the law, April’s father violently broke the intense ethical trust that bonds a father and his family. That situation calls April to act.

In the moment, Ram has just made a powerful confession of love and trust that she doesn’t know how to reciprocate, and might not be capable of reciprocating. A radically powerful development in a relationship of profound trust calls April to respond.

She summons all the strength she can to make the ethically best response – the consequences will be dealt with, but the response cannot be avoided.

This is a truth of justice.

• • •

Charlie’s confession is a combination of all these. An undeniable truth whose expression unburdens a corrosive secret, pulled from him by the sheer danger of the situation and the need of those he loved.

Yet it’s also a mistake of a sort, based on the folly of his perspective – his deep guilt that thoughts alone require the same ethical culpability as the act. The Rhodian (and Kantian, and Christian) morality that the desire for a crime is indistinguishable (in pure reason, or in God’s eye, respectively) from its commission.

And like all their truths, this is left hanging. Tanya is still alienated from her friends, Ram wounded and April alone, Charlie shouldered with an otherworldly guilt, and Matteusz hoping and doubting he can handle his love’s alien nature.

There will always be consequences. And so more confessions.

Just a few special effects like the classroom door floating in the blackness of no-space. The CGI shots of the transdimensional asteroids. The explosions and prop chaos during the asteroid crash and other shenanigans with a smoking asteroid. Everything else is carried on the strength of the dialogue and actors.

On those grounds of basic criticism, “Detained” delivers. Patrick Ness’ dialogue has its clunky moments as usual, but all the actors pull off some powerful, nuanced moments. The episode’s entire concept is about forcing the actors into intense literally confessional scenes. This is Doctor Who does No Exit. Literally.

Because,

SPOILERS

warned – they are genuinely in hell. A one-room prison in a pocket beyond space and time where their only way out means confessing their closest secrets about how they feel about each other to each other.

Many Kinds of Truth

So let’s get the basic premise out of the way. Quill puts the Scooby Gang in detention so they don’t mess with her while the events of the next episode are happening. A freaky asteroid smacks their classroom through the rift and knocks them into a no-space.

The asteroid turns out to be a prison for alien murderers. The only way to find out about their situation is to hold onto a piece of the asteroid and let it take you over. And when you channel the asteroid, it forces you into a confession. A suitable piece of mystical police state technology for the Whoniverse.

It isn’t just a matter of being forced to tell the truth. Truth is more complicated than just facts. Because the gang want to learn facts.

They each take their turn with the asteroid so they can learn enough facts about it and their situation to escape – they can each only handle the asteroid once before it fries their brains, the asteroid is a transdimensional prison, they’re trapped in their classroom with the consciousness of a multiple-murderer. And so on.

So far, so Doctor Who. Affordable TV budgets and high drama with cracking scripts, mad ideas, and quality actors. But since I’m doing philosophy at the same time as I’m talking about science-fiction television, I should ask – What kind of truths are we dealing with here?

Each of their interactions goes in the same pattern. They remember the most intense confession they’ve ever made (or almost made) before, then give a similarly intense confession about their friends in the cast, then force the asteroid/prisoner to reveal a secret about their situation.

Truth as Integrity

You confess so that the truth is known, because you’re compelled to say what’s true. This is why confessions are so powerful in the criminal justice – it’s literally the unfolding of truth. The burden of a secret is lost when it’s told. You don’t feel the pain of hiding anymore.

That’s Matteusz’ confession. He recalls coming out for the first time, to his dying grandmother, who knew from the start and didn’t care. The one member of his family who accepted him was the first to be told and also the first to leave. And he was left with the family who kicked him out.

That’s the same nature of his fear of Charlie, of Charlie’s alien nature, morality, capabilities. There is that deep love, but Matteusz’ fear slowly eats away at his love. Saying it lets them work it through and become closer for it. That’s the ethical confession.

Epistemic Truth

A confession is also how you see the world, how you understand what’s happening to you. Tanya’s first confession is of a shameful moment, when she continued to hide the fact that – after stealing a handful of candies as a child – she had planned from the start to steal. While she told her mother that she thought the sweets were free, that at the time she’d understood it not to be stealing.

Tanya’s confession to her friends is also about how she sees the world. She confesses her belief that she isn’t truly their friend because they think of her as a kid sister and not a peer, that they’ll never understand the kind of life and challenges she faces as a black woman in Britain.

What she confesses isn’t true in a factual sense – The rest of the gang are her friends, and while they may not all (except Ram, and oddly Quill) have experienced systemic social racism, as friends they can come to understand it themselves. The bonds of solidarity she doubts are really there.

Tanya’s is an epistemic confession, an expression of her own perspective on the world, which can be mistaken or incomplete while still being true. It’s the truth of how she sees the world.

The Facts

Then there is simply the factual truth. When you know something concrete about your world, and precisely. Typical for Ram, that’s his confession. He’s a stereotypical footballer again that way, always a simple soul. Saying what he thinks and doing what he wants. Heart on his sleeve no matter how hard (and badly) he tries to hide it.

Ram confessed to his father that he had an alien artificial leg. And he confessed to April that he loved her, but knew that she didn’t love him.

There it is. Behold! Check it out!

Responsive Truth

What do we learn from April? She’s a paradoxical character – Phil Sandifer is right that April’s paradoxes and subjective complexity makes her the most intriguing character on Class. But there’s more to these paradoxes.

April is notable for her personal strength to deal with immense burdens and traumas like her link with the Shadowkin and her father’s attempted murder-suicide. But the show first depicted her as this cloying school keener – the only one who cares enough about the school dance to set it up, even though everybody goes.

She doesn’t express her strength on her own. In ordinary situations, she’s content to be passive and unnoticeable, even if she’s lonely or isolated. Her strength only emerges in response to these terrifying challenges. She has a paradoxically weak strength – April is only an agent when she’s reacting.

So her confessions are reactions. She remembers testifying against her father in his criminal trial after his murder-suicide attempt – expressing a terrible, painful truth because the situation itself demands it. A confession that takes immense personal strength to make, but it would never have been made if not forced to.

What forces it? In the original instance, it’s the need to redress a terrible crime – more than having broken the law, April’s father violently broke the intense ethical trust that bonds a father and his family. That situation calls April to act.

In the moment, Ram has just made a powerful confession of love and trust that she doesn’t know how to reciprocate, and might not be capable of reciprocating. A radically powerful development in a relationship of profound trust calls April to respond.

She summons all the strength she can to make the ethically best response – the consequences will be dealt with, but the response cannot be avoided.

This is a truth of justice.

• • •

Charlie’s confession is a combination of all these. An undeniable truth whose expression unburdens a corrosive secret, pulled from him by the sheer danger of the situation and the need of those he loved.

Yet it’s also a mistake of a sort, based on the folly of his perspective – his deep guilt that thoughts alone require the same ethical culpability as the act. The Rhodian (and Kantian, and Christian) morality that the desire for a crime is indistinguishable (in pure reason, or in God’s eye, respectively) from its commission.

And like all their truths, this is left hanging. Tanya is still alienated from her friends, Ram wounded and April alone, Charlie shouldered with an otherworldly guilt, and Matteusz hoping and doubting he can handle his love’s alien nature.

There will always be consequences. And so more confessions.

A Lesson in Political Psychology, Research Time, 21/11/2016

Over the next few years in my different writing and art projects, one of the things I’ll do is try to understand the political phenomenon of Donald Trump.

I’ve been doing that on the blog for the last few weeks as I read some noteworthy radical democratic political theorists in the leadup and immediate aftermath of his election.

As my next big book Utopias comes together over the next few years, reckoning with the nationalist movement and whatever terrors his administration unleashes will provide the book’s context. So, aside from my general interest in global politics, I’m thinking through a lot of the most thoughtful accounts of what Trump means for human society.

One of those comes from Laurie Penny. Ever since reading her book Unspeakable Things a couple of years ago, I considered her a brilliant philosopher as well as an insightful and incisive journalist.

It’s weird in a lot of modern contexts to call someone who doesn’t work as a university academic a philosopher. But I think it’s increasingly necessary for philosophy as a tradition, given the pressures of academic institutions on creativity and social leadership beyond the community of university researchers.

Even in those circumstances, more and more university professors are too overburdened and underpaid to be leaders even in their community. Like too many people whose careers have been wrecked by casualization or automation, the sectors that are supposed to produce knowledge devote increasing amounts of energy to mere survival.

So it’s up to journalists and artists to understand and develop the concepts that bring us to such incredible danger and can save us. To understand nationalism and develop a path to liberation.

Penny’s article “Against Bargaining” is one example of the public, open-access, mass market philosophy that people who oppose racism, bigotry, nationalism, and autocracy need to read today. We need it to feed our minds and keep us sharp. To focus ourselves on the differences that make real differences, the basis of accurate, worthwhile action.

Nietzsche wrote about resentment as a seething, creeping social force. It was the cultural attitude that uses hatred to turn weakness into strength. But this isn’t the emboldening hatred of rage at an oppressor. It’s the petty small-mindedness of slimy disgust at anyone who dares to present themselves as your equal.

That’s one context of the attitude of resentment. It’s resentment triumphant, the decadent society of 19th century Europe, Europe at the heart of empire. Imperialism that was popularly justified by a morality of white supremacist racism.

The idea refuses to die. At least in some contexts. Homogeneously white affluent communities within spitting distance of more economically and ethnically mixed districts is one context. Places where no one knows enough non-white people to move their thoughts beyond stereotype and fear.

That petty attitude is also, at an individual level, the perspective of the abuser. He blames you for the violence he inflicts and you accept his narrative. Look at how many nice liberal journalists have written thinkpieces on how multiculturalism and identity politics caused President Trump.

You know what multiculturalism is? It’s living in a mixed community – walking down the street and passing by couples and families of as many possible ethnic and gender combinations as you can get out of a randomizer.

You know what identity politics is? It’s the assertion that your life and cultural heritage has value, especially if that life and heritage has been devalued and abused for generations.

It’s my fault that I’m being hurt because I stood up for myself and demanded that I not be hurt. If I’m compliant, then I won’t be hurt. I’ll be silent. I’ll be good.

To be good out of fear of an authority’s punishment isn’t goodness. It’s fear. The psychology of the abuse victim is to mask the outcome of overpowering fear as moral virtue.

Here, the psychological has become political. The most dedicated foot soldiers of Trumpism are the online trolls – abusers and harassers who are entertained by provoking more emotionally vulnerable people into mental distress. And who believe their own bullshit when they defend their violent actions as the exercise of their rights to free speech.

A movement of people who’ve learned to take pleasure in the psychological pain of others have taken their own will to violence to a mass-scale group phenomenon. Hence Penny’s astute observation – that the vulnerable people who are taking Trump’s ascent best have been those who have already overcome abuse.

People who’ve already worked through the self-cannibalizing philosophy of blaming yourself for the violence you suffer. We are facing today a political movement that literally wants to bludgeon dissent and difference into silence and invisibility. They see disagreement and ethnic, religious, or sexual difference as obnoxiousness.

Maybe you could call it getting uppity.

It’s our duty not to believe them and remember that rights to freedom aren’t meant to defend your attempts at violence. It’s to defend your attempt to be.

I’ve been doing that on the blog for the last few weeks as I read some noteworthy radical democratic political theorists in the leadup and immediate aftermath of his election.

|

| A traditionally realist depiction of President Trump, in a contemporary fresco. |

One of those comes from Laurie Penny. Ever since reading her book Unspeakable Things a couple of years ago, I considered her a brilliant philosopher as well as an insightful and incisive journalist.

It’s weird in a lot of modern contexts to call someone who doesn’t work as a university academic a philosopher. But I think it’s increasingly necessary for philosophy as a tradition, given the pressures of academic institutions on creativity and social leadership beyond the community of university researchers.

Even in those circumstances, more and more university professors are too overburdened and underpaid to be leaders even in their community. Like too many people whose careers have been wrecked by casualization or automation, the sectors that are supposed to produce knowledge devote increasing amounts of energy to mere survival.

So it’s up to journalists and artists to understand and develop the concepts that bring us to such incredible danger and can save us. To understand nationalism and develop a path to liberation.

Penny’s article “Against Bargaining” is one example of the public, open-access, mass market philosophy that people who oppose racism, bigotry, nationalism, and autocracy need to read today. We need it to feed our minds and keep us sharp. To focus ourselves on the differences that make real differences, the basis of accurate, worthwhile action.

Nietzsche wrote about resentment as a seething, creeping social force. It was the cultural attitude that uses hatred to turn weakness into strength. But this isn’t the emboldening hatred of rage at an oppressor. It’s the petty small-mindedness of slimy disgust at anyone who dares to present themselves as your equal.

That’s one context of the attitude of resentment. It’s resentment triumphant, the decadent society of 19th century Europe, Europe at the heart of empire. Imperialism that was popularly justified by a morality of white supremacist racism.