Brad Evans is another academic who wrote about Gilles Deleuze in the LA Review of Books.* He talks about a curious academic phenomenon, which I want to talk about in more detail. Let’s call it critical exhaustion.

* It’s been a few days since I last wrote about this series, so here are those links. Deleuze is a really important influence on a lot of my thinking and writing in non-fiction, arts, and in my daily life. But because most of that reading came before I started this writing blog, he isn’t always on it as often as he should be. At least explicitly.

|

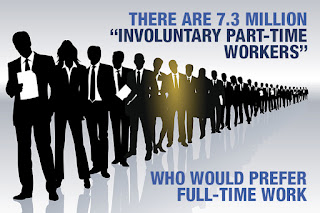

| The PowerPoint graphics of an exhausted generation. |

Exhaustion, generally speaking, is a pretty common concept among my generation. This is the generation of people in North America who entered the workforce through the last decade of recession.

We’re all desperately trying to build a respectable career and life in a social context where so many social safety nets have been stripped bare, and so much labour has been casualized or interned. Exhaustion and anxiety has become an ordinary state of mind. I’ve certainly felt that quite a lot lately.

But there’s a different kind of exhaustion, which I noticed was becoming dangerously common in my old field of academics. Evans makes a good summary, and it goes something like this.

Most folks in the philosophy discipline, especially those who specialize in “Continental” philosophy,** aren’t really encouraged to do creative work of their own. The cultural atmosphere of the field encourages them to build their research profiles writing secondary literature on major figures in their chosen sub-tradition.

** A false label if there ever was one. Basically, in North America, all the French and German writers in existentialist, phenomenological, structuralist, post-structuralist, radical political, or broadly post-modernist strains are called Continental. Europeans don’t really know what this word means.

|

| He is seriously the Gilles Deleuze of rap music. I will make this metaphor work. Somehow. |

In the 20 years since his death, Deleuze has blown up like Kanye in North American academia, at least among the Continental scholars. So a huge number of people started writing on Deleuze.

And the articles are flowing out of people and into journals*** at a skull-crushing pace. So many academics are stuck in precarious adjunct employment, that they’re desperate to grow their publications to land the shrinking number of tenure-track positions. So they produce an enormous number of articles on their chosen sub-disciplines and central figures.

*** Most of which are behind paywalls so high that even universities themselves can’t afford to stock them anymore. Countless articles that no one reads.

But they can’t just repeat what another scholar has said. Even in a culture that encourages coat-tail riding over real conceptual originality, you need to find your own take on your focal figure.

This ends up producing a research culture in philosophy that desperately uncovers as many possible interpretations of the various canonized writers as are plausible. Then the community moves on to the ridiculously implausible interpretations.

Like Daniel Smith’s career-long contention that Deleuze was a closet Kantian the entire time, or Alain Badiou and Peter Hallward’s case that Deleuze was actually a massive hypocrite who really believed the opposite of everything he wrote.

Evans thinks we’ve reached that point in Deleuze scholarship. That there’s not much else to get out of interpreting the man’s philosophy as such. But that doesn’t mean it’s over.

Critical exhaustion is the atmosphere in modern academia that exhausts these interpretations. More quickly than ever, what can be said about someone is exhausted. Everything sensible to say is already in someone else’s words. So the academic commentariat drifts away to tear into the next idol.

But real creativity isn’t piling these interpretations on top of each other. An interpretation is a creative act, but it doesn’t go as far as possible into the new. It’s just talking about something or someone.

Evans says that exhaustion can turn into defeat. Looking at Deleuze scholarship, and at the lives of an entire generation of North Americans, that appears to be the case. But it also means we can return to these books without the burden of having to talk about them.

Instead, we can talk with them, and develop new ideas and approaches to our common problems with these books as companions. Let the commentary die away for a while. Let’s start to think instead.

Let’s not think only with our favourite authors. Let’s think with each other, and maybe find solutions to the problems of our world.

No comments:

Post a Comment